Ted Lauterbach is the creator of suteF, an eerie and challenging platform puzzle game. We asked how how he goes about designing puzzles as part of our investigation into puzzle design.

A bit more about suteF: you pay a fragile blue character, you are in the Abyss, and you are trying to get out. You do this by reaching a television-screen in each level, and the challenge is to get to it, around eternal valleys and deathly lasers. You get to use boxes, switches, gravity switches…and a grappling hook to do this. On your way out, you will meet a creepy cast of characters. You’re only given a hint of story, but – supported by art and sound – it is a major contributor to the game’s atmosphere.

suteF was IndieGames’ top freeware puzzle game of 2010.

Ted Lauterbach answers our questions below.

Dev.Mag: What are the qualities of a good puzzle?

I’ve always thought that the best puzzles are ones that require the player to come up with unexpected ways to solve them. For instance, one puzzle may require them to use the mechanics introduced in the game in ways they never thought possible. I also love puzzles that have multiple solutions; I’ve giggled on several occasions when someone has solved one of my puzzles in half the steps I had designed it to take.

Dev.Mag: What process do you follow to design puzzles?

My puzzle design is always dictated by the mechanics. I’ll develop a gameplay mechanic, such as a grappling hook; after one or two puzzles that have introduced the player to the mechanic, the next step is combining the mechanic with old mechanics (use the grappling hook to pull and manipulate boxes, which until now, the player could only push).

I’d say that my process is heavily tied to the evolution of the game itself. I always make a mechanic, add some puzzles, make another mechanic, and add some more puzzles. I don’t think I’ve had a single puzzle drawn out on paper that I ever ended up using because the puzzle never takes shape until you’re already playing it like the player would.

That being said, I will start with the player’s position then the player’s goal. Once they are in place, I’ll put what I feel is an appropriate amount of obstacles between them and the goal. I’ll tweak and tweak until it feels… right. Mostly it’s a feeling I go off to know when it’s done. It’s awfully hard to explain it.

Dev.Mag: In a sequence of puzzles based on a small set of mechanics, how do you make sure the puzzles stay interesting?

Part of the process of making the puzzles interesting is getting into the game yourself and figuring out the maximum numbers of ways to use the mechanics, and making all of the mechanics work with each other.

Part of the process of making the puzzles interesting is getting into the game yourself and figuring out the maximum numbers of ways to use the mechanics, and making all of the mechanics work with each other.

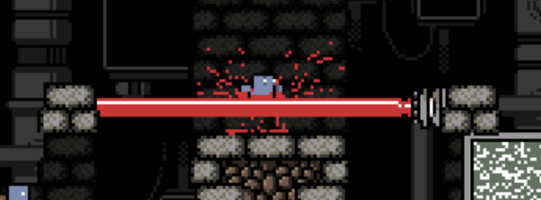

I can make a box. That is only one mechanic, but in suteF, that box does a lot: it can be pushed, pulled, flipped, climbed on, used to activate buttons, block lasers, and so many other things that it is ridiculous.

Adding a mechanic means that I get a chance to use old things in new ways, giving a fresh take on elements the player has already seen. It takes many puzzles for them to wear out, but when they do, the new interactions will be there to save the day.

Dev.Mag: How to you judge whether a puzzle is fun, and how difficult it is to solve?

Play testing with people who have never touched the game before is key. If they are stuck on a particular puzzle for too long, it means I haven’t made clear the mechanics that are involved in solving it. At that stage, I  have to make a decision: do I axe the puzzle because it’s too hard for the player this early on, or do I add another level that introduces them to the concept they’re missing?

have to make a decision: do I axe the puzzle because it’s too hard for the player this early on, or do I add another level that introduces them to the concept they’re missing?

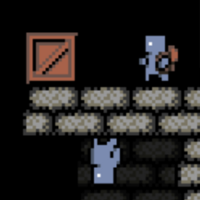

I recall one stage in suteF that I ran into this. Several people were stuck in a section that required them to jump while upside down. Even though there was no change to the playfield other than the player being upside down, no one thought they could jump. To alleviate this, I added a level before it that the only way to beat it (and the only thing to actually do) was to jump while upside down, then BAM! Everyone understood it. (See image left).

Dev.Mag: In suteF, you often give clues to the solution in the text. What other devices do you use to guide the player towards the solution, and help them understand the weird logic of the Abyss?

Visual cues are a large part of suteF. I will not obscure the elements that are  required to solve the puzzle. If a box needs to be used on top of a button, the button and the box had both better be easily distinguishable and visible. Nothing is more frustrating in a puzzle than obscured pieces; it would be like trying to put a jigsaw puzzle together with a piece missing at your aunt’s house. Or, if you intend to make them go to their aunt’s house (in a manner of speaking), you had better leave a trail of easily distinguishable and visible elements that can lead them there.

required to solve the puzzle. If a box needs to be used on top of a button, the button and the box had both better be easily distinguishable and visible. Nothing is more frustrating in a puzzle than obscured pieces; it would be like trying to put a jigsaw puzzle together with a piece missing at your aunt’s house. Or, if you intend to make them go to their aunt’s house (in a manner of speaking), you had better leave a trail of easily distinguishable and visible elements that can lead them there.

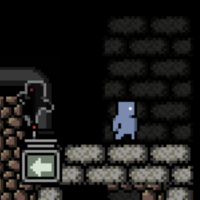

Early on as well, I introduced a ghost character in suteF that showed the player how to do some of the important actions.

Dev.Mag: Do you have any advice for those who want to design their own puzzles?

Start simple. The more moves it takes to solve a puzzle, the harder it is going to be. Ideally, your first puzzles will require no more than 2-3 actions. Inversely, a puzzle that has more paths to get to the solution will be easier. It leaves more room for error. The hardest puzzle in suteF had only one way to solve it, with only 20 very precise actions. No puzzle should take the average player more than 5-10 minutes to solve at their first go.

Also, operate under constraint if you want to make neat puzzles. Force yourself to get to know everything about your mechanics before you make new ones. Knowing them inside out will only make developing a puzzle easier.

Pingback: Indie Links Round-Up: Show of Hands | DIYgamer

Great interview. I loved, well, I enjoyed suteF. Love feels incorrect for such a dark game, haha!

Pingback: Ted Lauterbach??????????? | GamerBoom.com ???

Pingback: Indie Game Links: That ‘Whaaa’ Moment | Digital Combat Soldiers